....

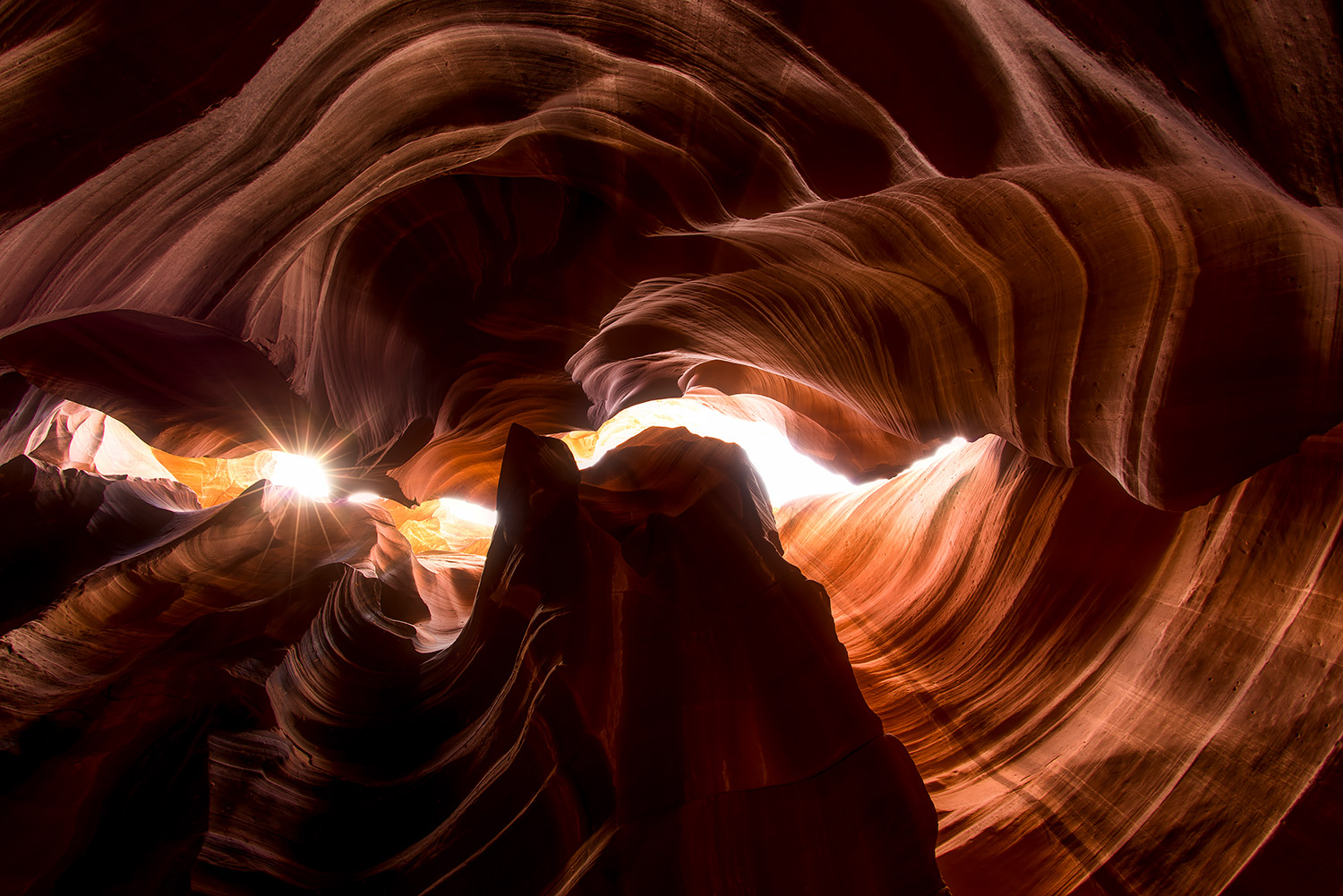

Die treibende Kraft in diesem Kapitel ist die Erosion. Werden Regionen über Jahrmillionen Wasser, Wind und Gletschern ausgesetzt, hinterlässt dies tiefe Spuren in Form von Canyons. Auf diese Weise erschuf die Natur auch den größten von allen, den Grand Canyon in den USA. Abhängig von der Gesteinsschicht und der Wasser- und Windmenge entstehen jedoch auch so-genannte Hoodoos (turmartige Formationen aus Sedimentgesteinen), Steinbögen, enge Slotcanyons oder sonstige Gebilde. Das Vorzeigebeispiel für ein perfektes Zusammenspiel aus Gestein und Erosion liefert der Bryce Canyon in Utah, USA. Hunderte feuerrote Hoodoos türmen sich hier auf einer halbkreisförmigen Abbruchkante hintereinander auf. Im Jahre 2011, nach zahlreichen Reisen in den Südwesten der USA, wurde mir die äußerst seltene Ehre zuteil, den Bryce nach einem tagelangen Blizzard in frischem Winterkleid zu fotografieren. Mit diesen besonderen Gebilden steht der Bryce Canyon jedoch nicht alleine da, denn auf dem gesamten Colorado Plateau lassen sich Tausende solcher Gegenden finden, von denen viele bereits zum Nationalpark ernannt worden sind. Gesteinsschichten sind die Bücher der alten Zeit. In ihnen lesen Geologen wie andere in Romanen – und wir Fotografen halten dies für die Nachwelt fest.

..

The driving force in this chapter is erosion. Areas exposed to the action of wa-ter, wind, and glaciers over millions of years receive deep scars in the form of canyons. This is how nature created the greatest of them all, the Grand Canyon in the United States. The quality of a given rock layer and different regimes of wind and water give rise to so-called hoodoos, which are turret-like formations of sedimentary rock, as well as to arches, narrow slot canyons, as well as other structures. In the United States, Utah’s Bryce Canyon is a model of the perfect coordination between rock and erosion. Hundreds of fire-red hoodoos overtop one another in successive rows along the semicircular canyon rim. In 2011, after numerous journeys in the American southwest, I had the utterly infrequent honor of photographing Bryce mantled in fresh snow after several days of blizzard conditions. But Bryce Canyon isn’t the only place to exhibit hoodoos. Across the entire Colorado Plateau, there may be thousands of spots like this, of which several have already been declared as national parks. The rock layers are the books of bygone eras. Geologists read them like others read novels, and we photographers record their appearances for posterity.

....